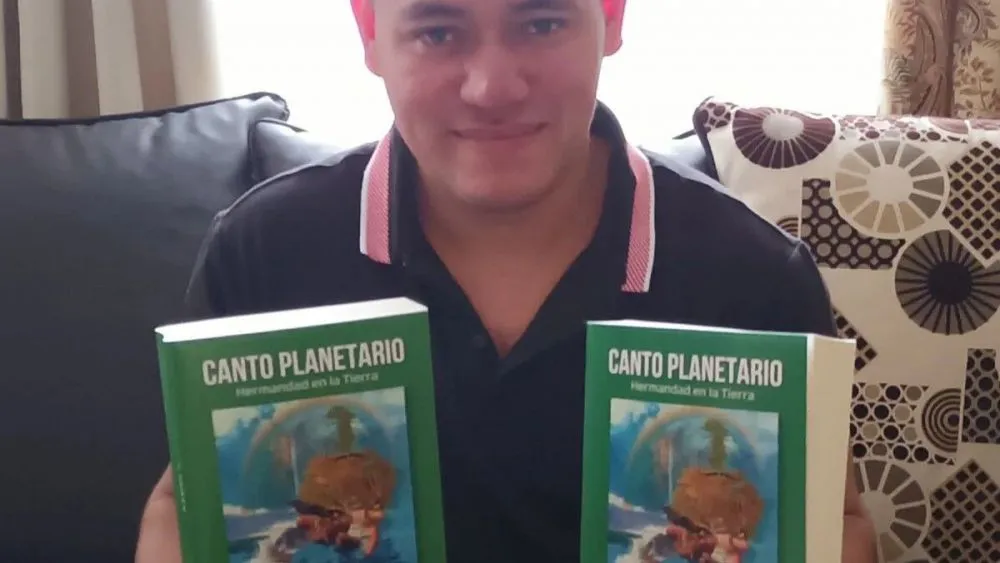

“Todas la voces todas”: el Canto Planetario concebido por Jarquín

Columnas - Esquina literaria y más...05/17/2025 Carlos Javier Jarquín

POSDATA Digital Press| Argentina

Por Carlos Joaquín Jarquín | Periodista, escritor, poeta, columnista internacional

Es verbo en lágrima” (1:411), del puertorriqueño Luis Enrique Romero, sea acaso uno de los versos que mejor condense la antología Canto Planetario: Hermandad en la Tierra (H.C EDITORES, Costa Rica, 2023), del joven compilador y escritor nicaragüense Carlos Javier Jarquín. Si sustraigo y trastrueco esas palabras de Romero, el conjunto de textos podría resumirse también en la frase “Y es lágrima en verbo”—una excreción enorme y entre salada y dulce, como el mar Caspio—. ¿Que por qué el llanto, pregunta usted? Se llora, al brote de palabras pergeñadas, por el estropicio de la Tierra, y, a la vez, por el desamor, las pérdidas, la ruindad, el abandono, la guerra, las enfermedades, las hambrunas, las inundaciones, la apatía, los prejuicios que cincelan golfos entre unos y otros seres… Ciertos versos surten amor, belleza, alegría o esperanza, pero, con frecuencia, en ellos algo perverso, y hasta inofensivo en apariencia, sale al paso. Así lo sugiere, por ejemplo, la brasileña Ester Abreu Vieira de Oliveira, a sus noventa años, en un estilo casi modernista: “En las cumbres argentinas / luz gélida resplandece, / lanza al mar / un velo de encajes azules / que en los claros bosques flotan / y se disuelven / al encontrarse con / cálidas aguas que / invitan a un caos climático” (1:127). Mientras Mbaї-adjim Timotheée, un poeta de Chad, de solo poco más de veinte años, cifra imágenes apocalípticas: “Los ríos se secan, las aguas aceitosas, los peces muertos, / miles de moscas corriendo hacia arriba y hacia abajo. / Pájaros muertos, perros, gatos hundiéndose / y causando enfermedades desconocidas” (1:17).

Dos volúmenes gruesos recogen quejidos (y hasta propuestas) de unos doscientos cincuenta escritores, articulados ante la tala indiscriminada, las selvas arrasadas, el envenenamiento de las aguas, el emponzoñamiento de los suelos, la desaparición de especies, la avalancha de plásticos descartados, el arrasamiento de bosques y selvas, entre otros males con que las criminales codicia e indiferencia apuñalan la naturaleza: “Ardientes y rojas motas vagan por los pantanos / huyen las sofocadas criaturas, arden las flores / el humo desgarra la atmósfera con desenfreno / los niños se aturden, no más izadas de banderas / ¿quién provoca este desastre?” (2:250), escribe Hartinah Ahmad en Singapur. Y la polaca Ewelina Maria Bugajska-Javorka nos conmueve con su pedido: “Llora, alma mía, / ¡Llora! / Humedece los labios de la seca tierra / ¡Haz que renazca su carne agrietada!” (2:450). Ante la destrucción que se presencia y lamenta, también encontramos instancias de reproche e imputación: “¿Y cómo evitar la destrucción del planeta?, ese es el interrogante del siglo que debe preguntársele precisamente a los jerarcas del mundo, a los líderes de las grandes naciones, porque ellos son los culpables por su afán de enriquecimiento y poder desmedido” (1:327). Este segmento corresponde al hondureño Mario Hernán Ramírez, el único escritor del conjunto ahora desaparecido —falleció tres meses antes de salir el libro—, ya que otro objetivo de Canto Planetario es dar a conocer creadores contemporáneos.Si bien hay en Canto Planetario otras piezas en prosa, como la citada de Ramírez, la poesía predomina en los dos volúmenes del compendio, de allí que les ajuste el vocablo Canto del título. Pese a la extraordinaria pluralidad de voces recogidas, es “canto” en singular pues lo alienta y concierta una angustia común ante la ruina de la celestial esfera veteada que habitamos. Es Planetario tanto porque los temas atañen a la desazón por la sobrevivencia de la Tierra, tal como la conocemos hoy, como porque los libros exhiben, en fotografías y voces, a representantes de países de los cinco continentes: África, América y Oceanía en el volumen 1 y Asia y Europa en el volumen 2. El subtítulo Hermandad en la Tierra alude al ideal de unión de los seres humanos, sin distingo de clase, fenotipo, origen, credo, edad, cultura. Apela a los aspectos que nos vinculan y, tácitamente, descarta los que podrían separarnos. Constituye además una invitación a que reclamemos y actuemos juntos para evitar las catástrofes que se ciernen. El proyecto cuenta con su propio himno y vídeo, disponibles en este enlace: Mi Canto Planetario (Vídeoclip oficial) /Himno de CANTO PLANETARIO

Los dos volúmenes supusieron un esfuerzo titánico del ideador Jarquín con su ingente equipo de colaboradores desinteresados. Sin apoyo económico institucional, los tomos reúnen a 268 personas de 110 países, con igual número de hombres y mujeres participantes. Hay contribuciones en árabe, bemba, igbo, bribri, maorí, setsuana, eton, quiché, maleku, urdu, lao, kaqchikel, ndelebe, tayiko, danés, kimeru, esloveno, kazajo, uzbeko, odia, kurdo, tagalo, maratí, ndebele, xhosa, tamil, entre 77 lenguas, algunas en peligro de extinción. Cada texto, transcrito primero en los caracteres propios de cada idioma, ha sido traducido al español. De un proyecto de esta magnitud y tanta apertura, no puede exigirse paridad en cuanto a la virtud lírica ni los estilos poéticos plasmados en sus páginas. Asimismo, en un contexto de preocupación ambiental, versos como los de la croata Ljubica Katić, que podrían no estar dirigidos al mundo, sino a un amante, se resignificarían como un llamado a disolver las distancias para encontrarnos: “Esta noche, déjame tocar el cielo, / dispersar la nube que nos mantiene separados” (2:436).

El inmenso poeta peruano César Vallejo parecería haber dudado de la trascendencia de la palabra cuando escribió: “¡Y si después de tantas palabras / no sobrevive la palabra! / ¡Si después de las alas de los pájaros, / no sobrevive el pájaro parado! / ¡Más valdría, en verdad, que se lo coman todo y acabemos!”. En contraste, un proyecto como Canto Planetario demuestra una fe resuelta en el poder de la palabra. Brilla el optimismo de Jarquín. Que la palabra unificadora, sensibilizadora, comprometida, educadora, difusora de tantos hombres y mujeres viaje muy lejos y se eleve muy alto y, al fin, en un coro húmedo por lágrimas de alegría, llueva gozosa sobre la Tierra recobrada.

Dr. Beatriz Carolina Peña obtuvo su maestría en The City College of New York y el Ph.D. del Graduate Center (CUNY), donde este 2025 ha merecido el Premio a los Logros de Exalumnos o Alumni Achievement Award. Ha publicado artículos en revistas y volúmenes especializados. Sus libros han recibido diversos galardones en Estados Unidos, España, México, Perú y Cuba. Se ha desempeñado como profesora en varias universidades estadounidenses y, actualmente, es catedrática en Queens College (CUNY).

Dr. Beatriz Carolina Peña obtuvo su maestría en The City College of New York y el Ph.D. del Graduate Center (CUNY), donde este 2025 ha merecido el Premio a los Logros de Exalumnos o Alumni Achievement Award. Ha publicado artículos en revistas y volúmenes especializados. Sus libros han recibido diversos galardones en Estados Unidos, España, México, Perú y Cuba. Se ha desempeñado como profesora en varias universidades estadounidenses y, actualmente, es catedrática en Queens College (CUNY).

All Voices, All: the Planetary Song Conceived by Jarquín

"And it is word in tears" (1:411), by Puerto Rican poet Luis Enrique Romero, is perhaps one of the verses that most powerfully distills the essence of the anthology Canto Planetario: Hermandad en la Tierra (Costa Rica: H.C. Editores, 2023), compiled by the young Nicaraguan writer Carlos Javier Jarquín. If one were to transpose Romero’s line, the collection might also be encapsulated in the phrase “And it is tear in words"—a potent metaphor, evoking a mingling of fresh and salty waters, like those of the Caspian Sea.

Why the tears, one might ask? These verses weep—for the degradation of the Earth, for the absence of love, for loss, ruin, abandonment, war, disease, famine, flood, apathy, and the prejudices that carve chasms between human beings. Some poems offer moments of love, beauty, joy, or hope, but often something darker, even deceptively benign, rises to the surface. This tension is reflected in the work of Brazilian poet Ester Abreu Vieira de Oliveira, now in her nineties, whose style bears traces of Spanish Modernism: “In the Argentinean summits / icy light shines, / throws to the sea / a veil of blue lace / that in the clear forests float / and dissolve / when meeting / warm waters that / invite a climatic chaos” (1:127). Meanwhile, Mbaï-adjim Timotheée, a poet from Chad still in his early twenties, offers apocalyptic imagery: “Rivers dry up, oily waters, dead fish, / thousands of flies running up and down / dead birds, dogs, cats sinking / and causing unknown diseases” (1:17).

Two thick volumes gather the woes, protests—and even proposals—of some 250 writers, united in response to indiscriminate logging, razed jungles, poisoned waters and soils, vanishing species, the deluge of discarded plastics, and other wounds inflicted on nature by criminal greed and widespread indifference. “Fiery red motes roam the marshes / flee the suffocated creatures, burn the flowers / smoke tears the atmosphere with recklessness / children are dazed, no more flag-raising / who causes this disaster?” (2:250), writes Hartinah Ahmad from Singapore. From Poland, Ewelina Maria Bugajska-Javorka moves us with her plea: “Weep, my soul, / Weep! / Moisten the lips of the dry earth / Make its cracked flesh be reborn” (2:450). Amid mourning and warning, some voices rise in reproach and accusation: “And how to avoid the destruction of the planet? That is the question of the century, one that should be asked directly to the hierarchs of the world, to the leaders of the great nations, because they are to blame—for their eagerness for enrichment and excessive power” (1:327). These are the words of Honduran writer Mario Hernán Ramírez, the only contributor who had passed away—just three months before the anthology’s publication. One of Canto Planetario’s aims, after all, is to amplify the voices of contemporary creators.

Although Canto Planetario includes prose works—such as the aforementioned piece by Ramírez—poetry predominates across the two volumes, making the word Canto (Song) in the title especially fitting. Despite the extraordinary plurality of voices, canto appears in the singular—a unified song rising from shared anguish. It is Planetario (Planetary) not only because the themes address the urgent question of Earth’s survival as we know it, but also because the books feature voices and

photographs of contributors from across all five continents: Africa, America, and Oceania in Volume 1; Asia and Europe in Volume 2.

The subtitle, Hermandad en la Tierra (Brotherhood on Earth), invokes the ideal of human unity—regardless of class, race, origin, creed, age, or culture. It emphasizes the bonds that unite us and, implicitly, rejects the divisions that threaten solidarity. It is also a call to collective responsibility: to act together in the face of looming catastrophe. The project even includes its own anthem and video, available at the following link:

project even includes its own anthem and video, available at the following link: Mi Canto Planetario (Vídeoclip oficial) /Himno de CANTO PLANETARIO

The creation of these two volumes was a titanic effort led by Carlos Javier Jarquín and a vast network of dedicated, unpaid collaborators. Without institutional financial backing, the project succeeded in bringing together 268 contributors from 110 countries, with equal representation of men and women. The anthology includes texts in 77 languages—among them Arabic, Bemba, Igbo, Bribri, Māori, Setswana, Eton, Quiché, Maleku, Urdu, Lao, Kaqchikel, Ndebele, Tajik, Danish, Kimeru, Slovenian, Kazakh, Uzbek, Odia, Kurdish, Tagalog, Marathi, Xhosa, and Tamil—some of which are endangered. Each piece is first presented in its original script and then translated into Spanish.

From a project of this scale and openness, uniformity in lyrical quality or poetic style cannot be expected—nor should it be. The value lies in the breadth of human voices it gathers. Even verses that might initially seem personal or romantic take on new meaning in the context of global ecological concern. Consider these lines by Croatian poet Ljubica Katić: “Tonight, let me touch the sky, / disperse the cloud that keeps us apart” (2:436). Though they may speak to a lover, they resonate as a metaphorical call to dissolve divisions and rediscover our shared humanity.

The great Peruvian poet César Vallejo once seemed to question the very endurance of language when he wrote: “And if after so many words / the word does not survive! / If after the wings of the birds, / the standing bird does not survive! / It would be better, in truth, that they eat it all and we end up!” In contrast, a project like Canto Planetario affirms a resolute faith in the power of the word. Jarquín's optimism shines through each page. May the unifying, sensitizing, committed, enlightening, and far-reaching words of so many men and women travel wide and rise high—until, at last, in a chorus drenched in tears of joy, they rain gently upon a restored Earth.

Beatriz Carolina Peña earned an M.A. from The City College of New York and a Ph.D. from the Graduate Center, CUNY, where she just received the 2025 Alumni Achievement Award. Her scholarly work includes articles published in specialized journals and edited volumes. Her books have garnered multiple awards in the United States, Spain, Mexico, Peru, and Cuba. She has held teaching positions at several U.S. universities and is currently a full professor at Queens College, CUNY.

“Un llanto sefardí”, canción interpretada en español y hebreo

Estreno mundial de la canción:Ese es mi libro

El 23 de abril se celebra el Día Internacional del Libro y en honor a tan distinguida fecha se reunieron, escritores y profesionales audiovisuales de todo el mundo y produjeron la canción: "Ese es mi libro"

La Justicia en debate: La expresidenta y el sistema legal

Cuando el mundo calla, la paz se desangra: Irán, Israel, EE. UU. y el colapso de la gobernanza mundial

A quienes se eligieron. A quienes se escucharon en voz bajita, pero igual se creyeron.